Written by Thierry Ng & Corrine Naisbitt.

When Corrine Naisbitt lost her husband Richard to mesothelioma, she turned her grief into action. Now a member of the National Centre for Asbestos Related Diseases Consumer Advisory Panel, Corrine shares their story – not just of illness, but of love, endurance, and community. From a farming life in Lake Grace to the corridors of research meetings at NCARD, her voice now helps guide the future of asbestos-related disease research.

Mesothelioma remains one of Australia’s most aggressive cancers, caused by asbestos exposure. Corrine’s account is a reminder that while asbestos use has ended, the legacy is not over – and neither is the work. Her story is also a tribute to the partnerships between researchers and the community that underpin NCARD’s approach.

________________________________________

The dust never leaves you. Not the red earth of Lake Grace that clings to work boots and settles in the creases of sun-weathered hands. Not the asbestos dust that looked like snow falling on two young people building their first fence, laughing as they sawed through fibro sheeting, calling themselves snowmen. Especially not that dust.

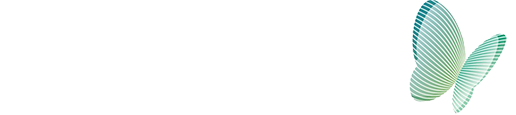

Corrine Naisbitt sits in the ordered quiet of NCARD Consumer Advisory Panel meetings, her voice carrying the weight of someone who has learned that advocacy is another form of love. After farming at Lake Grace and Newdegate, then running a surf shop in Joondalup for twenty years, she thought the hardest chapters were behind them, partially retiring to Dunsborough in 2013 with her husband, Richard. A year later, their lives would cleave in two – before and after a mesothelioma diagnosis.

The Architecture of a Life Together

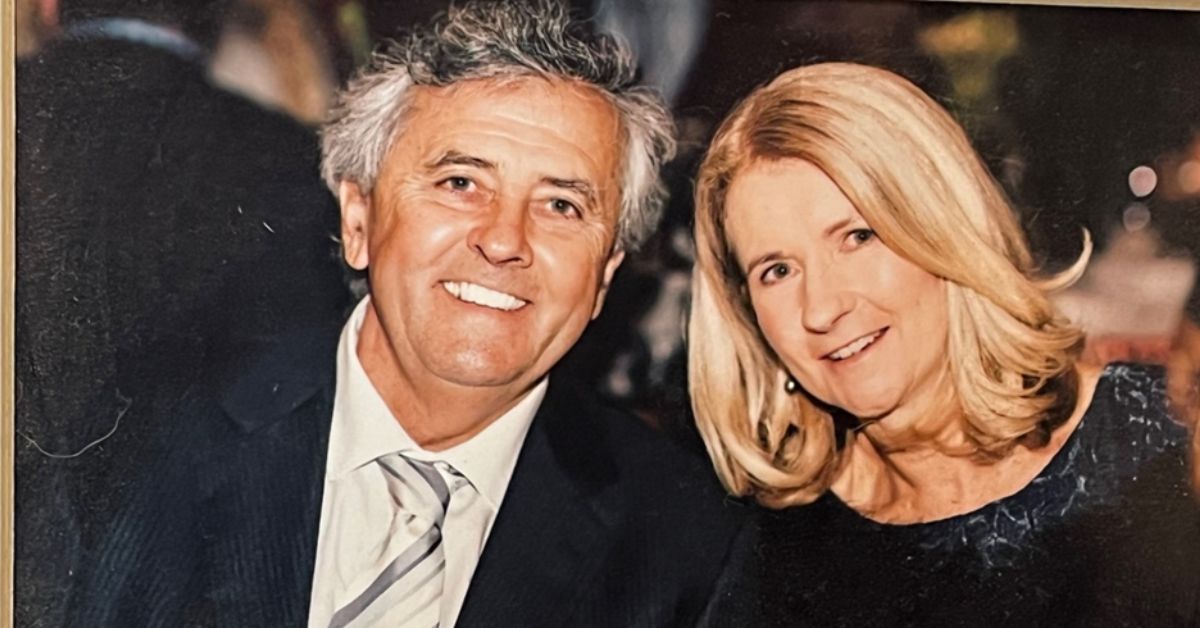

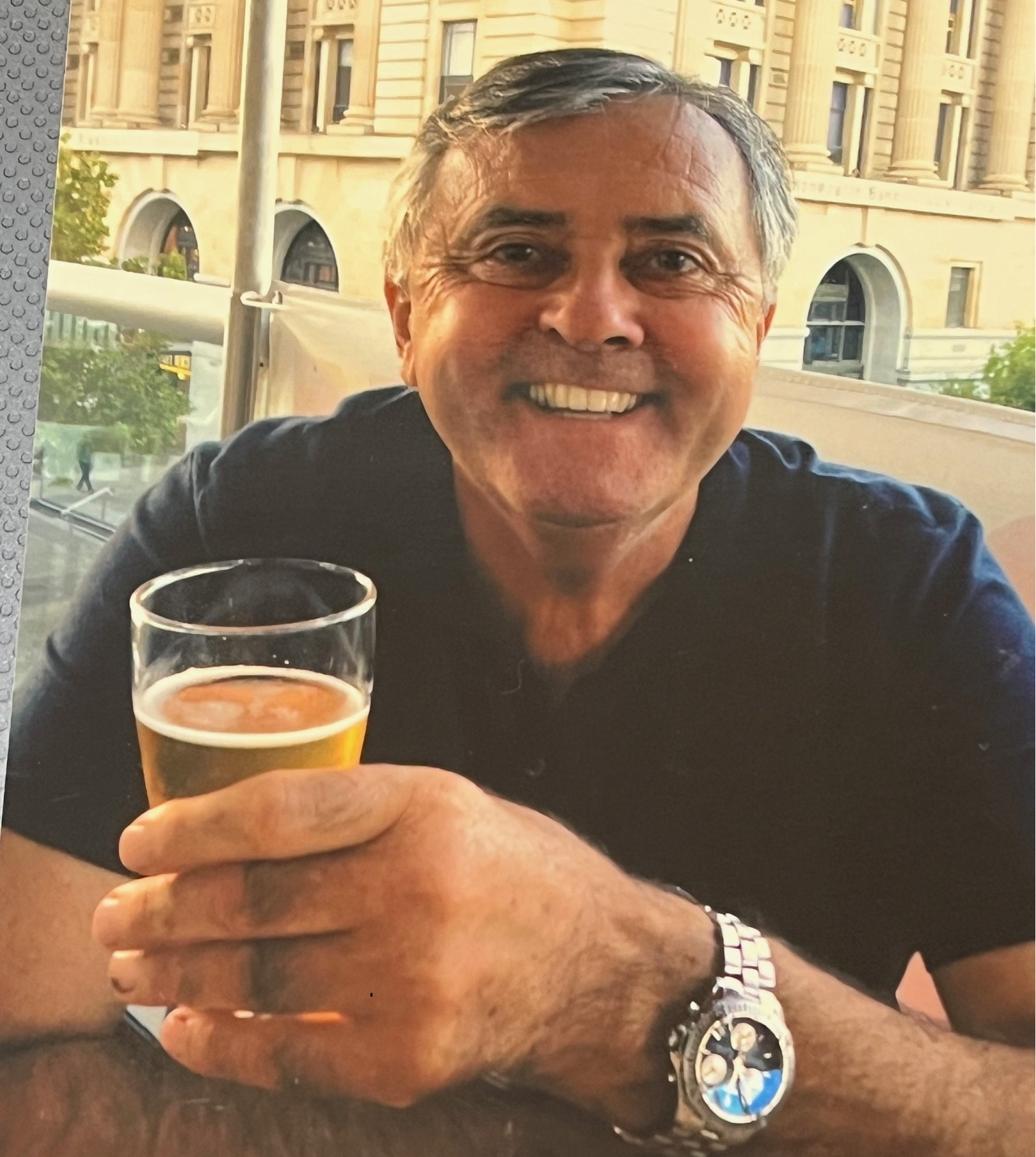

In the beginning, there was Richard’s laughter echoing across football fields and tennis courts, his feet pounding the dirt track up Bluff Knoll where he unofficially broke records – simply because he could. Richard Naisbitt was one of seven children, built for motion and music, his hands equally at home with a piano, guitar, or harmonica as they were steering hot rods around the local track.

“He was very fit and athletic. Played football, tennis, and golf and was pretty much excellent at all. In his youth, he was a very good long-distance runner, and once, he ran up Bluff Knoll, unofficially breaking the record time. He loved fast cars, raced hot rods, and Super Modifieds at the local Hot Rod Club. He loved Elvis, Chubby Checker, Ray Charles, Dolly Parton and AC/DC and could play the piano, guitar and harmonica,” said Corrine.

The couple married in 1975, weaving together threads of ambition and devotion that would hold for forty-four years. In Lake Grace, that small town cradled by the Great Southern’s endless sky, they built their first dreams. Richard worked the shearing circuit while Corrine found her place at the Shire office, both learning the particular rhythm of country life where everyone knows your name and your business.

Then came 1978 and the kind of decision that changed everything: 5,000 acres of scrubland at Newdegate, waiting to be transformed. It was a Conditional Purchase block that existed more as a possibility than a reality. An untamed bush that would be chiselled into a farm.

“Looking back, we certainly were crazy and probably a little naive, but always optimistic and hard working.”

The bush fought them every step of the way. Richard kept his shearing team running while attacking the scrub with machinery that roared against the silence of dawn. Corrine took on extra work, and Richard filled weekends with handyman jobs – painting, tiling, anything that brought in money to feed their growing dream.

“We worked very hard, always together and with lots of laughs.”

The farm breathed with their efforts, expanding into something successful, something that worked. But success has its own complications. By 1994, their eldest daughter, Kathryn, was starting high school, disappearing into boarding school corridors, and both parents ached at her absence.

Perth called to them then, promising proximity to family, and they answered by selling their green acres and diving into the salt-spray world of retail – a surf shop at Joondalup. This became their new frontier, with twenty-one years of working side by side, learning the tides of commerce, the seasonal rhythms of tourist trade and local custom.

“Once again, we worked together, something we always did well.

“We moved to Dunsborough in 2013 to retire – or try to. We weren’t very good at the retirement bit.”

Dunsborough was a reward for a lifetime of dawn starts and aching backs. The wine-dark ocean stretched toward a horizon that seemed infinite, and for the first time in decades, time belonged to them. Long lunches with friends. Travel to places they’d only imagined. The weight of Richard’s arm around her shoulder as they watched sunsets paint the sky in shades of contentment.

The Cough That Changed Everything

The cough arrived quietly, the way dangerous things often do. A persistent tickle followed Richard from room to room, accompanied by a tiredness that afternoon naps couldn’t cure. In a man who had run up mountains and wrestled farms from scrubland, fatigue felt foreign, unwelcome.

“Not long after we moved down south, Richard had a cold and light cough which never seemed to go away, and he was experiencing tiredness and often felt like an afternoon nap.”

But Richard had always carried a dark knowledge in the back of his mind. A cousin had died of mesothelioma, and the word lurked in family conversations like an uninvited guest.

Of the cough, he would often joke, “Oh, it’s my meso.”

In early 2014, Dr Nick Carr looked at Richard’s X-ray and saw shadows that shouldn’t exist. The suspicious cloudiness led directly to Dr Mark Edwards, the cardiothoracic surgeon in Perth, and tissue samples that would either confirm their worst fears or set them free.

The day the results came back, their world tilted on its axis.

“I will never forget the day Richard came home from seeing Dr Nick Carr with the results. It was mesothelioma. Richard walked in the door, fell into my arms and cried.

“And so began life with mesothelioma. A battle, Richard said. He despised the word journey.”

The asbestos had been waiting all along, microscopic time bombs lodged in lung tissue, counting down the decades. After leaving school, Richard travelled north to building sites in Geraldton and Darwin, breathing in fibres that looked harmless as dust motes lounging in afternoon light. Back in Lake Grace, renovation work on GEHA homes was heavy with asbestos, and construction on the Sportsman’s Club with its asbestos roof – each job was another deposit in a toxic bank account that would eventually come due.

Even their personal projects had been contaminated. The asbestos fence around their first home was too difficult to dig into clay soil, so they sawed off the tops, laughing as white dust settled on their clothes and hair.

“I can remember joking ‘we looked like snowmen’ as we were covered in dust. We had absolutely no idea of the dangers of asbestos. This was in 1975.

“In reality, most people of our era, particularly in the country, were exposed. Our homes were mostly asbestos, asbestos fencing, asbestos was put down on railway lines, and many appliances contained asbestos.”

The Territory of Treatment

In the beginning, Corrine wanted to wrap Richard in cotton wool, perhaps to shield him from the effects of the disease or the diagnosis. The impulse was maternal, desperate, and human. She hoped it would keep him well longer.

Richard’s diagnosis wouldn’t diminish him. Every day life became an act of defiance, and strength became Corrine’s daily offering to the man who worried more about her future than his own.

The Asbestos Diseases Society of Australia (ADSA) became their first lifeline. Rose Marie Vojakovic, who co-founded the organisation with her husband, Robert Vojakovic, guided them through the labyrinth of what lay ahead. This led them to NCARD researcher and oncologist Professor Anna Nowak at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, who understood that truth-telling was a form of compassion.

“Rose Marie organised us to see Anna Nowak at Sir Charles Gardiner Hospital, one of the best in this field and a wonderful human being. Never sugar coating anything, but hugely supportive.”

Even facing the impossible, Richard’s essential optimism blazed through. Standing in Anna’s office, diagnosis confirmed, prognosis delivered, he made a declaration that was pure Richard – audacious, charming, absolutely sincere.

“I’m going to be the first person to beat this insidious disease,” he said.

“That was Richard, always optimistic, always smiling, charming and stoic.”

August 2014 brought the first chemotherapy trial: Cisplatin and Alimta, chemicals with names like incantations, poured into Richard’s veins in the fluorescent-lit treatment rooms of Charlie’s. Even here, his humour endured, questioning Anna with mock suspicion: “Are you sure you haven’t put water in instead of the drugs?”

They grew familiar with the hospital’s corridors. The dreaded rhythm of treatment cycles: chemotherapy, scans, respiratory clinic, blood tests.

“The staff at Charlie’s were always amazing. It became our home away from home, if that doesn’t sound too weird.”

Crawford Lodge, a self-catering accommodation lodge provided by Cancer Council WA, provided sanctuary in the storm. It was a place where they could walk to treatment instead of trudging through Perth traffic from Dunsborough.

“Richard and I made up a playlist for the endless trips to Perth and would drive home singing, laughing, and also, crying multiple tears.”

The disease demanded its tribute in blood and tissue – Richard’s body becoming a site of research as much as treatment. He gave willingly, understanding that his cells might hold answers for others, even as the constant needle sticks wore at his patience.

“In the end, he hated giving blood, and we named the research lady ‘Dracula’.”

Against all odds, Richard’s sheer force of will carved out space for joy. Two trips north with friends who understood that laughter was medicine. They journeyed to Korea and Dubai to see their youngest daughter, Hayley, living with her husband.

The treatment years unfolded in waves: more chemotherapy in 2015 and 2016, a trial with Linear in 2017, and additional chemotherapy with radiation in 2018. Each round brought hope and exhaustion in equal measure, living scan to scan, always balanced on the knife-edge between reprieve and progression.

“It becomes a life of highs and lows, from one scan to the next.”

The Circle That Held Them

The couple never faced mesothelioma alone. Richard’s openness about his diagnosis became a gift to their community, creating space for others to show up, to share the weight.

“Our most helpful support probably was our amazing lifelong friends who were always there. Richard never hid his disease from anyone and always talked openly and honestly with his friends and family. After every scan, they would all ring and share the good or the bad. I cannot thank them all enough.”

“His mates would come out every couple of days and share a cuppa with him, have a good laugh, and solve the problems of the world. A welcome respite from me, I’m sure.”

For Corrine, caregiving became a complex choreography of strength and tenderness. She took over the property maintenance that had always been Richard’s domain, working under his watchful supervision, learning to navigate the delicate balance between helping and diminishing.

“It was a privilege to be Richard’s carer. I had to take on most of the responsibility for our small property. I might add with Richard’s close supervision. Sometimes he needed help with basic day-to-day stuff.

“I tried really hard to be strong but not make him feel emasculated. This was important.”

The logistics alone were staggering: appointments, medications, and the careful tracking of treatments and side effects. Their life revolved around treatments, and Corrine became the keeper of their medical calendar, attending every consultation and treatment with Richard, creating continuity in a system that could feel overwhelming.

When the end came, Richard was surrounded by love, his dignity intact until the final moment.

“Richard had expressed that he did not want to go into the hospital or palliative care. I looked after him at home, but on his final day, it became impossible for him to stay at home.”

Richard Francis Naisbitt was admitted to the Busselton Hospital Palliative Care Unit mid-morning and passed away later that night on April 2, 2019, with his family gathered close. He had lived five years with mesothelioma, well beyond the twelve to fourteen months initially predicted; each extra day was a victory of will and love.

The Voice That Remains

Corrine’s eldest daughter, Kathryn, spotted an advertisement seeking consumer representatives for NCARD, recognising in her mother the voice that other families facing mesothelioma needed to hear.

“Eager to do something to honour Richard and possibly help other sufferers, I applied and was successful.”

In the conference rooms where researchers gather to discuss new treatment strategies, Corrine brings something irreplaceable: the lived experience of what this disease takes from families, the understanding that behind every statistic is a love story interrupted.

“I find this involvement very fulfilling, although at times, I feel a little overawed. This is an amazing team of researchers who work incredibly hard to find a successful treatment, for which I am very grateful.”

Her advocacy extends beyond formal meetings into the daily work of changing minds. Fundraising walks where she ropes in friends and family. Countless emails to politicians for more grant funding. Petition signatures and donations, the small acts that accumulate into pressure for change.

“I spread the word in my community of the dangers of asbestos and the need for research funding. I have participated in the ADSA fundraiser walks, roping in my friends and family for donations.”

The political work brings its own frustrations. Emails disappearing into the void of political indifference. Media outlets that seem uninterested in a disease seen as ‘over’ and ‘uncool’, perceived as only affecting older adults from Wittenoom.

The reality is more complex and threatening.

The Weight of Terminal

“I think people need to understand that mesothelioma is a terminal disease that can touch anyone. Unlike a lot of cancers, there is 0% chance of survival. People need to understand that asbestos is still around us, and it indiscriminately chooses victims. It’s a silent killer.

“That consultation, when they confirm the diagnosis and lay out the fact that you are not going to survive, is soul-destroying.

“You feel quite helpless.

“The impact on families is huge. Your life changes forever. The sun goes out. I felt like my heart had been torn from me. Richard was my husband, my best friend, my soulmate. The effects on our daughters were massive and took years for them to come to terms with it.

“Our older grandkids were particularly close with Richard. The effect on them has been huge.”

Conversations with the Departed

More than five years after Richard’s death, Corrine has learned to live with absence as a form of presence. Their conversations continue, one-sided now but no less real for being unheard.

“We all still ‘chat’ with Richard often. I talk to him every day. Weird, I know, but comforting. And every time I don’t put the tools back in the correct place, I can feel his frustration!

“I am slowly piecing life back together, although it will never be the same. I still live in Dunsborough, involving myself in community life and working casually a couple of times a week, which I love. I have amazing family and friends, and am fortunate enough to be able to travel a lot.”

Wisdom Born of Loss

Corrine’s advice to families facing mesothelioma comes from the deepest place of understanding: someone who has walked every step of the journey and emerged changed but not broken.

“To those of you out there going through this, be strong. Hold your loved ones close. Remember to laugh and find pleasure in the little things. Be honest with your family and friends. I know it’s hard, but be positive.”

The practical wisdom is equally important: the need to seek support, to come prepared to medical appointments, and to understand that isolation makes everything harder.

“Reach out for help. Don’t try to navigate this by yourselves. There is a lot of help out there. Ask questions at every consult, and if you don’t understand something, speak up. We found it helpful to take along written questions, as once in a consultation, you can be overwhelmed and forget what you wanted to ask.

“Put your hand up to help with research, whether through extra blood tests or tissue samples.”

Perhaps most importantly, she speaks about hope not as denial but as defiance, the refusal to let statistics define the entirety of experience.

“Richard was given a 12-14 month life expectancy from initial diagnosis. We had five years, and I believe that Richard’s positive outlook contributed to this. He saw our youngest daughter get married, and our third grandchild be born in that extra time.

“Most of all, have hope. There is always hope.”

The Research That Matters

Through her work with NCARD, Corrine ensures that research remains connected to its human purpose. Her presence in meetings reminds us that behind every grant application and study protocol are people like Richard and families like theirs.

“I hope that we can bring a personal perspective to mesothelioma, to make the research real for them and offer a different perspective. I also hope that I can help them in their endless pursuit of grants.”

Her message to the researchers is simple but profound: their work matters not just as science but as hope made tangible.

“Anything that can help, so future sufferers can have at least a chance of beating mesothelioma, is worthwhile. I hope it also helps the researchers see that what they do does matter.”

The Memorial That Lives

In the end, advocacy becomes another form of love, a way of keeping Richard’s story alive in service of others who will face the same battle. Be it through consumer advocacy, fundraising, or the simple act of telling their story, Corrine ensures that mesothelioma patients and families won’t face the journey alone.

The dust settles eventually, but memory endures – in meetings where research strategies are planned, in the stories shared between newly diagnosed families, and in the gradual shift of public understanding that comes from putting human faces on medical statistics.

Richard’s optimism lives on in Corrine’s advocacy. His belief that this disease could be beaten finds expression in her work toward better treatments, better support, and better outcomes for the families who will follow in their footsteps.

________________________________________

Richard Francis Naisbitt

11/07/1950 – 02/04/2019

Husband of Corrine, much-loved Father of Kathryn and Hayley,

Adored grandad of Eva, George, Winnie and Olivia

Father-in-Law and friend to Luke and Sam

A Good Bloke